Putting the New Dietary Guidelines Into Real-World Context for Families With Babies and Kids

If you are a parent, there is a good chance you have never read the Dietary Guidelines for Americans from cover to cover. And yet, these guidelines shape our children’s nutrition every single day.

When the 2025-3030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans were released, headlines quickly followed. As is often the case with nutrition guidance, complex recommendations were reduced to bold claims that are leaving many parents confused, frustrated, or unsure about whether they are feeding their children “correctly.”

This reaction is understandable. Feeding babies, toddlers, and kids already comes with enough pressure, and nutrition guidance should support families and meet them where they are. Feeding children is not about perfection. It is about practicality, reality, affordability, access, science, nuance, and individuality. Psychology, culture, and family dynamics play enormous roles as well.

With these concepts in mind, my goal in this post is to take a deeper look at what the new Dietary Guidelines do well, where they fall short for families with children, and how parents can use them to support both physical health and a healthy relationship with food.

What Are the Dietary Guidelines and Why Do They Matter for Kids?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans are updated every 5 years to reflect the latest nutrition science. While they are written for the general population, they influence school meals, WIC food packages, childcare nutrition standards, and national food policy that affects what foods are available, affordable, and promoted to families.

For parents, these guidelines often become a reference point, even if indirectly. Pediatricians, dietitians, schools, and policymakers rely on them, which means the way they are written and presented matters deeply for families with babies and kids.

It is also important to clarify what dietary guidelines are and are not responsible for. Previous guidelines did not cause rising rates of chronic disease, like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Much of the increase in chronic disease risk is driven by the Standard American Diet, which is typically low in fiber, high in added sugars, and heavily reliant on ultra-processed foods. These are eating patterns that dietary guidelines have never recommended.

What the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines Get Right

Before focusing on the areas of debate, it is worth acknowledging the positive contributions reflected in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines. Several recommendations are well-aligned with current pediatric nutrition science and offer helpful direction for families raising babies and children.

Emphasis on Whole, Nutrient-Dense Foods: The written recommendations continue to prioritize fruits, vegetables, and minimally processed foods. This aligns with strong evidence supporting overall dietary patterns rather than single “superfoods” or nutrients.

Guidance for Infant and Toddler Feeding: The guidelines appropriately emphasize developmentally appropriate feeding, including diet diversity, readiness for solids, timing of complementary foods, prioritizing milk feeds during the first year, and repeated exposure to new foods.

Attention to Key Infant Nutrients: The importance of vitamin D and iron during infancy is addressed, including acknowledgement that supplementation may be needed.

Support for Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding recommendations align with current American Academy of Pediatrics guidance. This reinforces breastfeeding as the best, evidence-based option for infant nutrition when possible, while still allowing families to make their own choices.

Encouragement of Food Skills and Family Involvement: The guidelines promote cooking with children and teens and encourage their involvement in food preparation and planning. This supports the development of food skills, autonomy, and healthier relationships with food over time.

Continued Support for Early Allergen Introduction: The guidelines continue to support early allergen introduction, which is reassuring for families. While many pediatric nutrition professionals would welcome updates beyond the 2017 NIAID Addendum Guidelines, maintaining this recommendation reinforces practices that reduce the risk of food allergy.

Brief discussion of gut health: The guidelines highlight fermented foods such as kefir, kombucha, and kimchi, as well as fiber-rich foods, as supportive of a healthy gut microbiome. While this section is small, it reflects growing recognition of the role gut health plays in overall wellness.

Where the Dietary Guidelines Fall Short for Families With Babies and Kids

Translating population-level recommendations into everyday feeding decisions for children is not always straightforward. When viewed through a pediatric and family-centered lens, several gaps and inconsistencies make the guidelines harder to apply in real life. Let’s take a look at the shortcomings of these new guidelines.

Missing Practical Guidance for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Teens

One of the biggest gaps in the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines is the lack of clear, specific, centralized guidance across the childhood age groups. The 2020-2025 guidelines were groundbreaking because they provided nuanced, evidence-based, age-specific detail on pediatric nutrition during infancy and toddlerhood for the first time, as well as each subsequent stage of childhood. As a pediatric dietitian and parent, I heavily relied on that clarity and specificity in day-to-day counseling, writing, and when designing nutrition programs, meal plans, and presentations.

In contrast, the current version lacks guidance on topics families ask about constantly, including:

Unsafe foods such as honey and unpasteurized products

Beverage guidance for water, juice, plant-based milks, and toddler milks

Key micronutrient needs across developmental stages and how to obtain them

Specific daily and weekly intake targets for food groups and subgroups for children of each age and stage to support their macro- and micronutrient needs

Support for vegetarian or vegan dietary patterns in childhood

Proper storage and handling of human milk and infant formula

Donor human milk

Added Sugar: Why “Zero Until Age 10” Lacks Nuance

Reducing added sugar is an essential public health goal. However, recommending complete avoidance of added sugar until age 10 oversimplifies feeding children in the real world.

Feeding kids is not just about nutrients. The psychology of food matters deeply, and from a pediatric perspective, overly rigid rules can increase parental guilt and unintentionally create power struggles around food. While nobody is encouraging more added sugars, research shows that strict avoidance often leads to fixation on sweets, sneaking behaviors, and shame.

Small amounts of added sugar can also play a functional role. A child who eats maple syrup-roasted vegetables or yogurt lightly sweetened at home is having a very different nutritional experience than a child who avoids vegetables and fermented foods altogether.

The guidelines also advise avoiding all artificial sweeteners, flavors, dyes, and preservatives. While it is reasonable to encourage moderation and reduce reliance on highly sweetened foods, this recommendation does not fully reflect the current body of evidence demonstrating the safety of these ingredients when consumed within established limits.

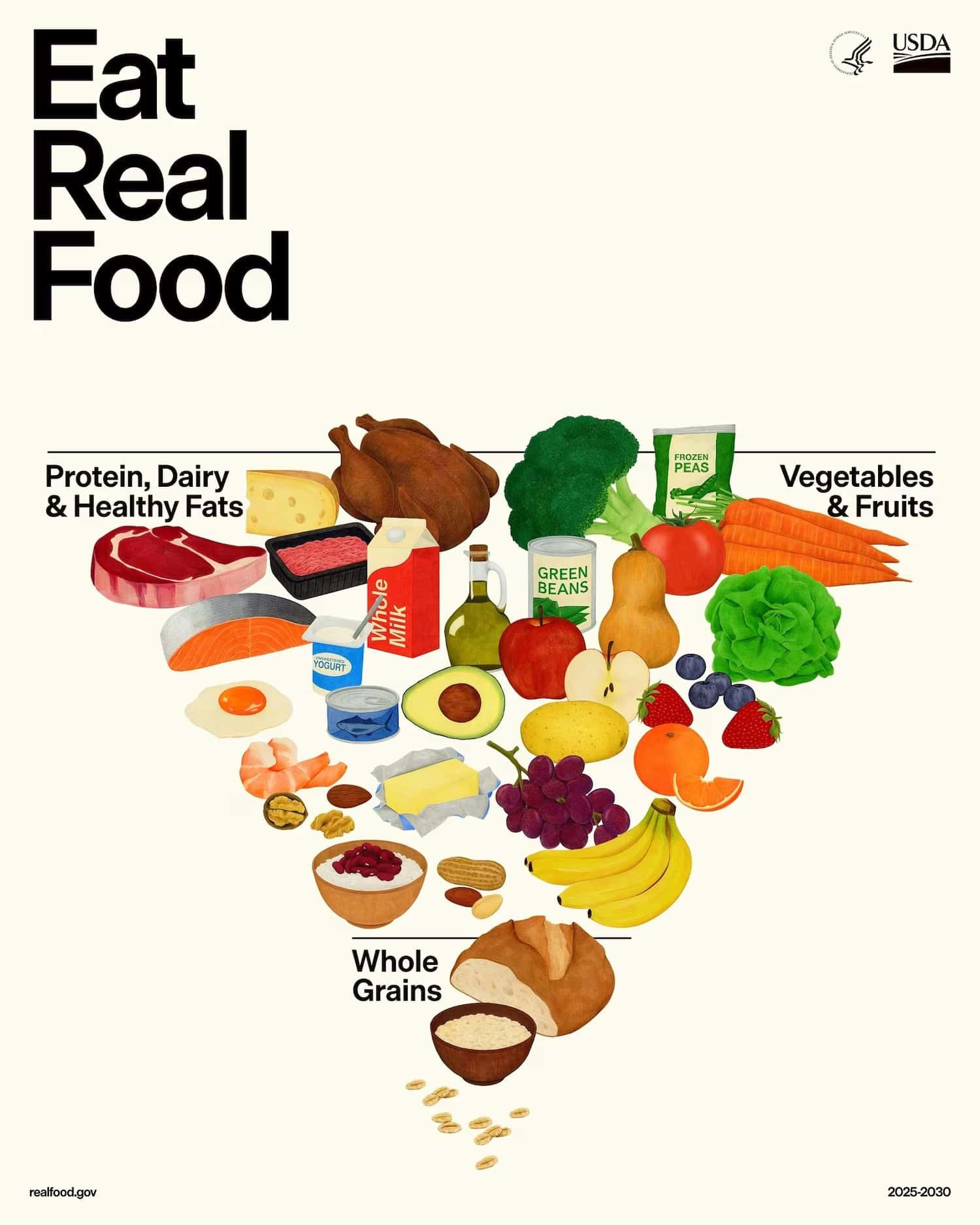

Confusing Visuals That Conflict With Written Recommendations

The updated food pyramid, now shaped like a funnel, has sparked debate across the nutrition community. While the written recommendations are generally sound, the visual undermines their clarity.

Foods higher in saturated fat, including red meat, cheese, butter, and beef tallow, appear visually emphasized, despite the recommendation to limit saturated fat to less than 10 percent of total calories.

At the same time, whole grains are pushed to the bottom of the funnel, even though the guidelines encourage regular intake of whole-grain foods. This is particularly confusing given that carbohydrates are the body’s primary source of energy and provide essential nutrients such as fiber, B vitamins, and iron.

For children, carbohydrates are the preferred fuel for growth and energy, accounting for about 45 to 65 percent of daily calories. For toddlers ages one to three, only about 5 to 20 percent of calories are recommended to come from protein, making the visual imbalance especially misleading for families.

Protein vs. Fiber: A Misplaced Emphasis

Protein is clearly prioritized in the new guidelines; however, true protein deficiency in children is rare in the United States.

Fiber inadequacy, on the other hand, is the real concern. More than 95 percent of Americans do not meet fiber recommendations. Despite this, fiber lacks clear intake targets in the 2025-2030 guidelines, and fiber-rich foods like whole grains and beans are visually de-emphasized, even though the written guidance supports them.

From a pediatric nutrition perspective, this represents a missed opportunity to address one of the most widespread nutritional gaps affecting both children and adults. Fiber continues to receive less emphasis than protein, even though fiber insufficiency affects digestive and heart health, and long-term disease risk across the lifespan.

While it is encouraging to see both plant and animal protein sources included, the visual guidance clearly emphasizes animal-based proteins. Plant-based proteins such as beans appear lower in the inverted pyramid, despite strong evidence supporting their role in fiber intake, gut health, and cardiometabolic health.

Dairy-Centered Guidance Without Adequate Alternatives

The new Dietary Guidelines place a strong emphasis on dairy but offer limited guidance for families who cannot or choose not to consume dairy products. This includes the 2-3% of children with cow’s milk protein allergy, and those with lactose intolerance, medical conditions, and families whose cultural practices or personal values limit dairy intake.

While dairy is a convenient source of calcium, vitamin D, protein, and fat, it is not the only way to meet these nutritional needs. The guidelines would be more practical if they provided clearer, age-specific pathways for meeting key nutrients through non-dairy foods and fortified alternatives.

Additionally, while evidence supports feeding full-fat dairy to children up to age 2 to support growth, brain development, and energy needs, the evidence beyond age 2 is less clear, and more research is needed. After this age, overall diet quality, growth patterns, family history, activity level, and access to a variety of foods matter more than the fat content of milk alone, meaning whole milk can still be a reasonable choice, but is not the only “right” option for every child.

“Eat Real Food” Messaging Without Addressing Real Life

The message to “eat real food” is well-intended but risks oversimplifying the realities many families face. Access, affordability, time, safety, and stress all shape what feeding kids looks like day to day.

Nutrition guidance cannot exist in a vacuum. If families lack access to food, safe housing, healthcare, and community supports, no set of dietary guidelines alone can create a healthy population.

While the written recommendations emphasize whole, minimally processed foods, there is little discussion about how families are expected to access or afford these foods. The guidelines also do not offer practical guidance on how to help children gradually shift from highly processed foods toward less processed, whole-food patterns, a transition that can be challenging for many families navigating time, budget, and food access constraints.

It is important to note that many processed foods, such as canned goods and pre-packaged dips like hummus, can help fill nutrient gaps, support food security, and make balanced meals more achievable and affordable.

The Bottom Line for Parents

In the end, the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines offer several positive, high-level, evidence-based messages, particularly around early feeding practices and family involvement in food. However, despite these strengths, many pediatric healthcare providers, myself included, are disappointed in the lack of clarity, nuance, specificity, and practical detail that made the 2020–2025 Guidelines such a trusted and actionable resource for supporting families in real-world settings.

For families with babies and kids, the goal is not perfection. It is raising children who are nourished, growing, and developing a positive, intuitive relationship with food. Dietary patterns matter more than individual foods. Flexibility matters. Culture, celebration, and joy matter too.

If feeding your child feels confusing or stressful, individualized guidance from a pediatric dietitian can help translate broad recommendations into realistic, supportive strategies that work for your family in real life.

And for those interested in the original, science-based recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, the Uncompromised Dietary Guidelines offer a clearer, evidence-aligned alternative. The Uncompromised Guidelines show what the Dietary Guidelines could have looked like if they had fully reflected the expert scientific review, without political or industry influence.

And if you are looking for more help with starting your baby on solids, check out my new book, Safe and Simple Food Allergy Prevention: A Baby-Led Feeding Guide to Starting Solids and Introducing Allergens with 80 Family-Friendly Recipes.

It includes a complete plan for allergen introduction, 8 weeks of baby-led feeding meal plans, a guide to starting solids and baby-led feeding based on the latest research, and 80 family-friendly recipes.

Thanks for reading!